Socialization of Knowledge Extractivism - Agri-Stack in India

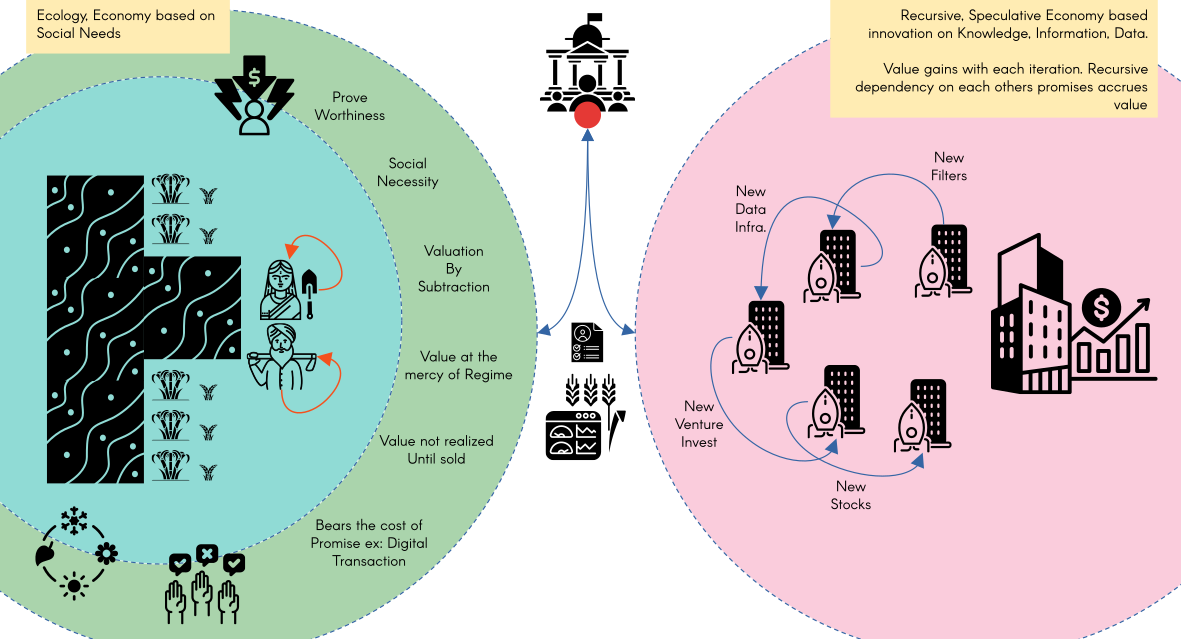

Promise of technocratic thought processes to alleviate socioeconomic problems have been elusive.Often, justification of the promise, comes with a narrative about an imagined future,which tends to be a historical.Various algorithmic and mathematical apparatus act as instruments to embody and carry that imagination, in order to project such promises as deliverable solutions. Such apparatus mediates between reality of social needs, a process imbued with layers of abstraction. Such exercises in abstraction manage to convert real world issues into symbolic problems, and mostly stop at that. Debates and discourse over how real world problems ought to be solved when mediated by this apparatus,however, have not made much difference to the lives of the working people.

A dominant version of this apparatus today, are the current structures of information and technology. The social and political processes which shape these structures need to be subject to scrutiny. Through this scrutiny, then it becomes possible to unpack how the promise of solving social needs remains elusive, in particular sectors in society.

In this essay, we would like to illustrate this problematic by choosing to study the issue of guaranteed fairness in the calculations of price for agricultural produce in contemporary India. We take up the recent federal Government initiative to build what is called Agri-Stack as a particular case. But before we get to this, it is important to understand the idea of a Minimum Support Price for agricultural produce and crop insurance in the Indian context.

Minimum Support Price(MSP) and Crop Insurance(CI):

The Minimum Support Price, hereafter referred to as the MSP, is defined as the:guaranteed rate at which the Government shall procure the produce from the farmers, directly. But this is not a subsidy. The idea of crop insurance is to compensate the farmer in case of risk to the crop due to natural calamity including floods and drought. Both these are intended to provide a safety net for farmers and to encourage the fundamental productive activity in agriculture. Below, we give a brief chronology of these two ideas in practice, since the 1960’s.

Year |

Minimum Support Price |

Crop Insurance |

Prior to 1965 |

Post-independence focus on nation building and agricultural development to ensure food security, but no clear version of MSP |

No significant crop insurance schemes |

1965 |

Agricultural Prices Commission (APC) set up to advise on pricing policies- FCI established for procurement at guaranteed prices |

Early pilot crop insurance schemes in a few states |

1985 |

APC renamed as Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP)- CACP begins recommending MSP based on cost of production |

Comprehensive Crop Insurance Scheme (CCIS) introduced |

1999 |

CACP continues to recommend MSP for various crops |

National Agricultural Insurance Scheme (NAIS) launched, replacing CCIS |

2006 |

MS Swaminathan Report recommends MSP at least 50% higher than the cost of production |

No significant changes in crop insurance schemes |

2007 |

CACP continues to recommend MSP based on various factors |

Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme(WBCIS) launched as a pilot scheme |

2010 |

CACP continues to recommend MSP based on various factors |

Modified National Agricultural Insurance Scheme (MNAIS) introduced |

2016 |

CACP continues to recommend MSP based on various factors |

Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) launched, replacing NAIS, MNAIS, and WBCIS |

2018 |

Government announces MSP for all unannounced crops to be fixed at least 1.5 times the cost of production |

PMFBY undergoes modifications and improvements |

2020 |

CACP continues to recommend MSP based on various factors- Farmer protests highlight the demand for legal guarantees on MSP |

PMFBY undergoes further changes to make it more farmer-friendly and affordable |

Some key aspects to mention are:

- Farmer Support: Both MSP and crop insurance schemes promised to support farmers, with MSP focusing on price stability and income support, while crop insurance protects farmers from crop losses due to various risks.

- Sequential Development: The evolution of MSP and crop insurance schemes has been sequential, with each building upon previous policies and addressing emerging challenges.

- Complementary Roles: MSP and crop insurance schemes play complementary roles in agricultural policy. While MSP ensures a minimum price for crops, crop insurance provides financial protection against crop losses.

- Policy Interaction: Changes in MSP and crop insurance schemes often reflect broader policy priorities, such as food security, farmer welfare, and sustainable agriculture.

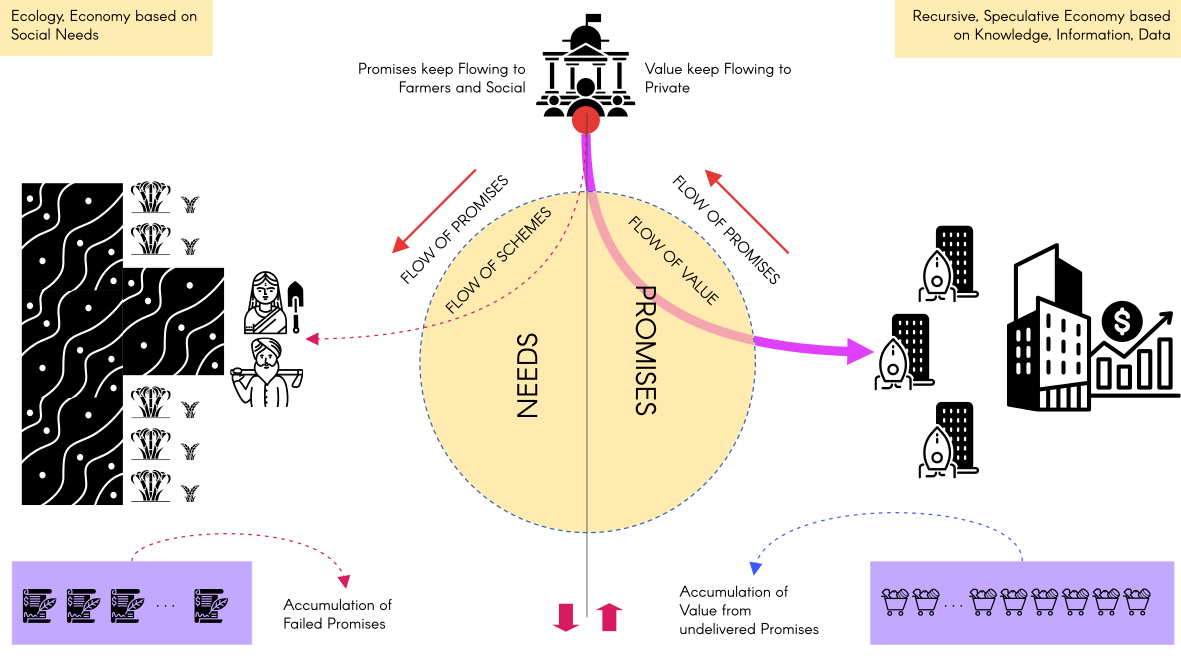

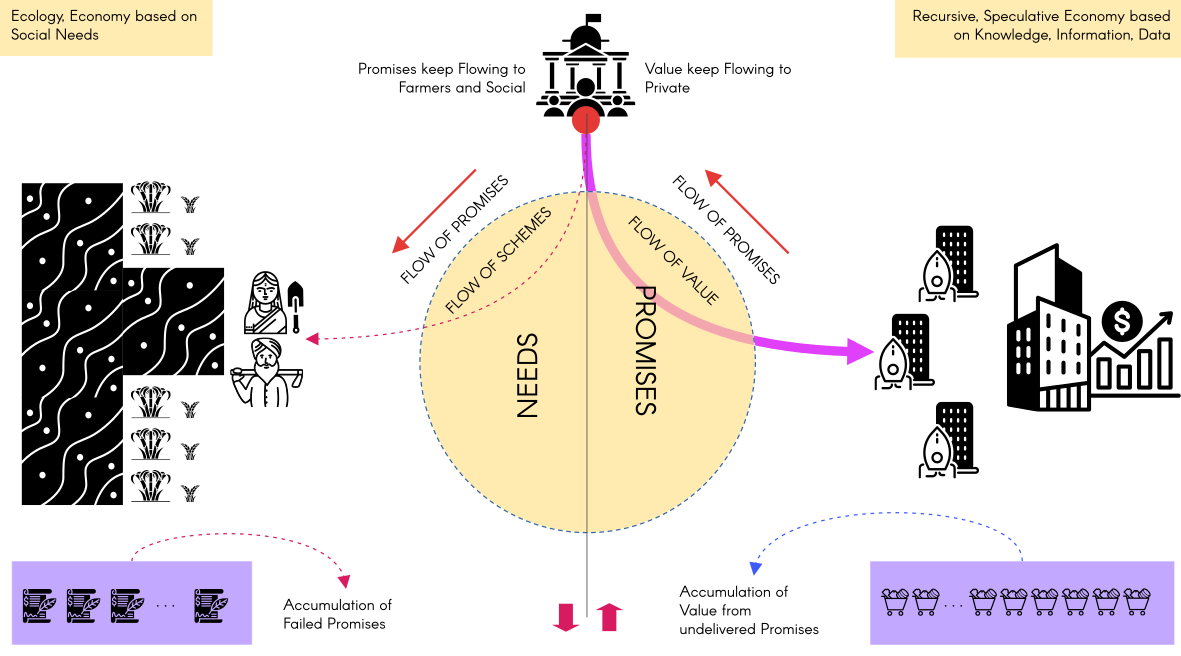

In summary, the tabulated chronology demonstrates the government's queue of promises (since 1960’s till 2020) to support farmers and promote agricultural development through a combination of price support and risk protection measures.

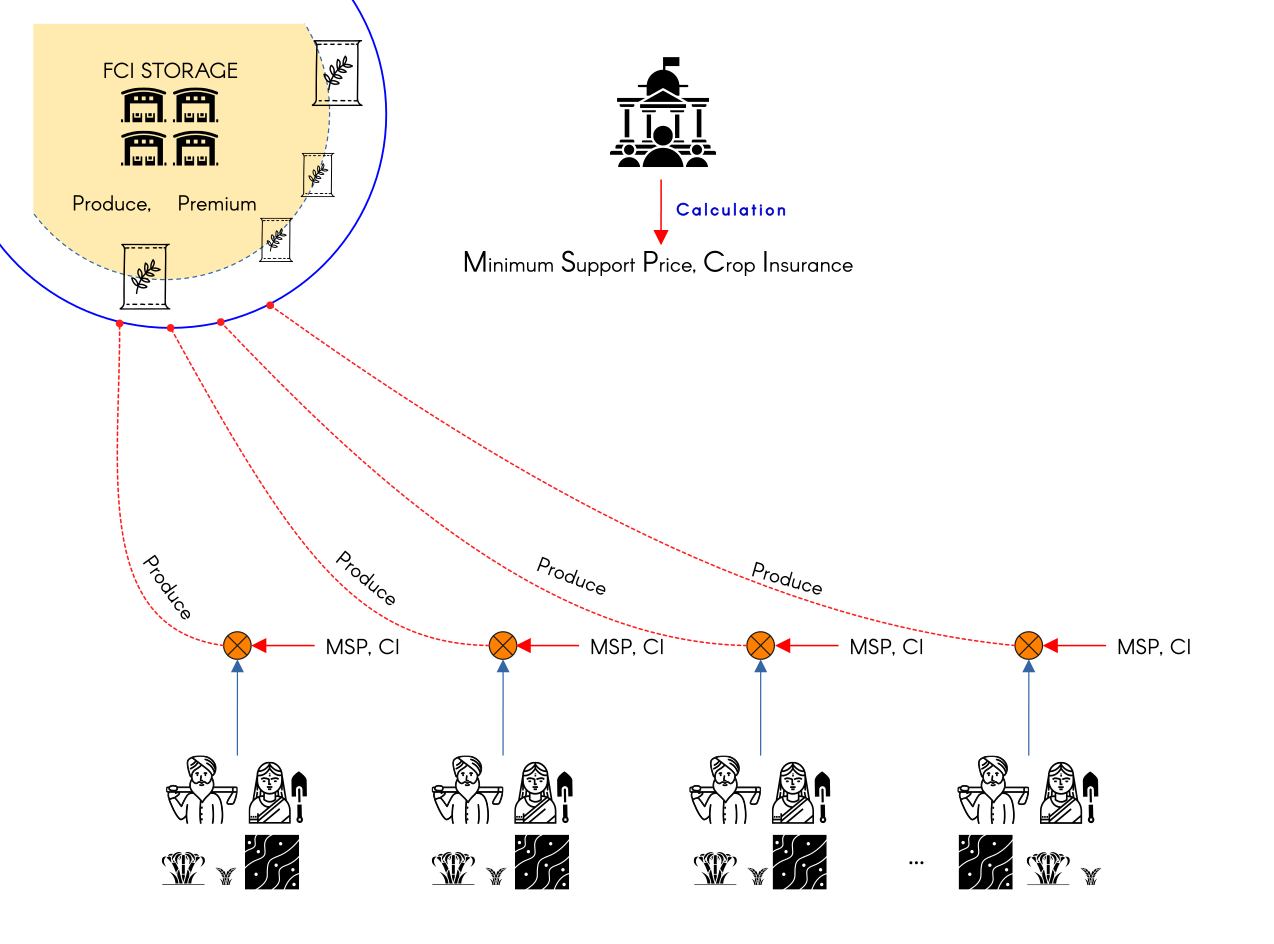

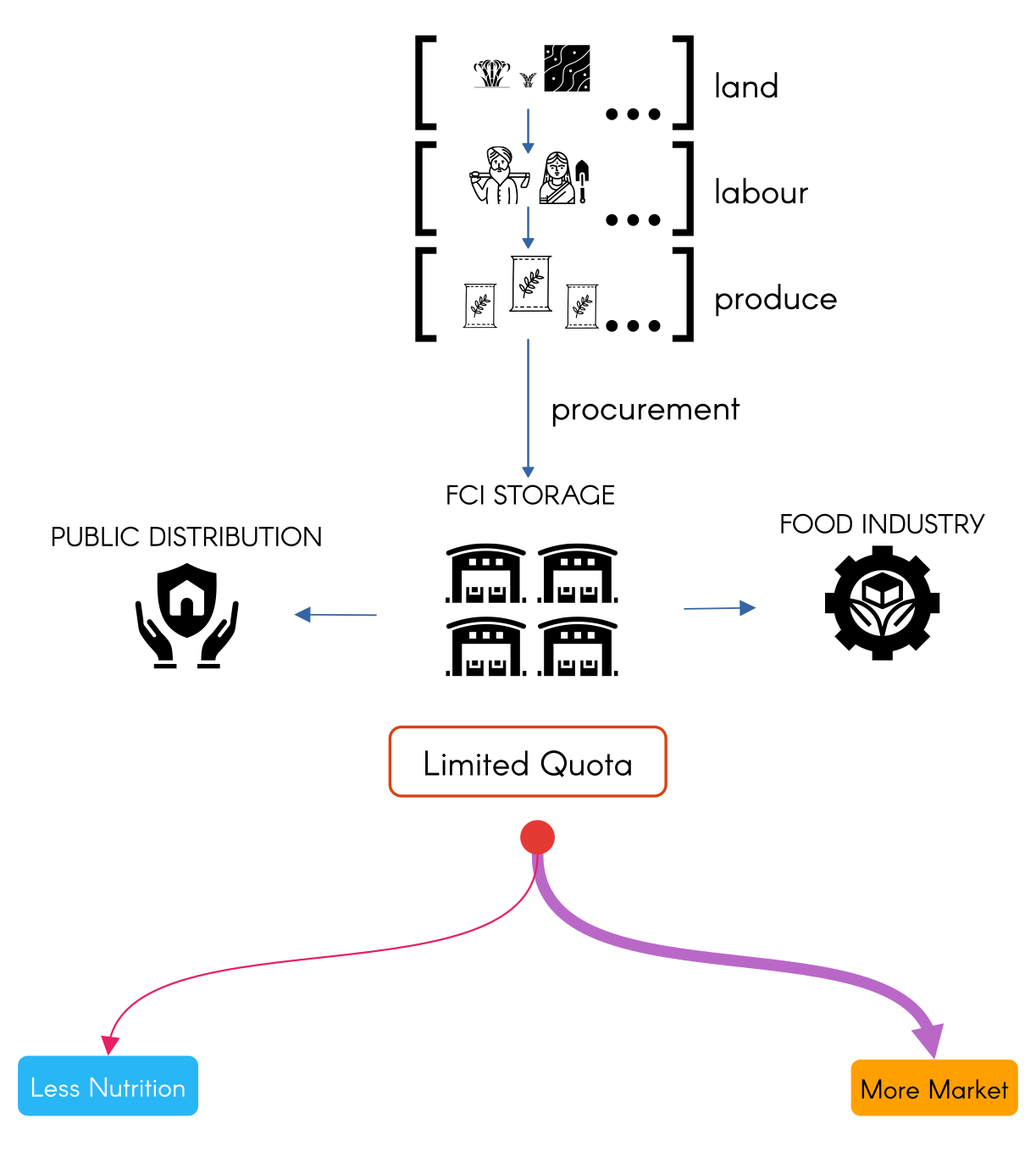

The key institution here is the Food Corporation of India, established to procure agricultural produce at guaranteed minimum support price based on the recommendations by the CACP. The FCI also serves the important function of holding food stocks as a mark of sovereign mandate to serve its people, in the event of a food crisis (such as a famine) or to serve the needs of the people through the Public Distribution system. FCI is the primary point of interaction between the farmers, their produce, the state’s mandate towards storage and distribution, and last but not the least, also its stock as the basis to value current produce through the mechanism of the minimum support price.

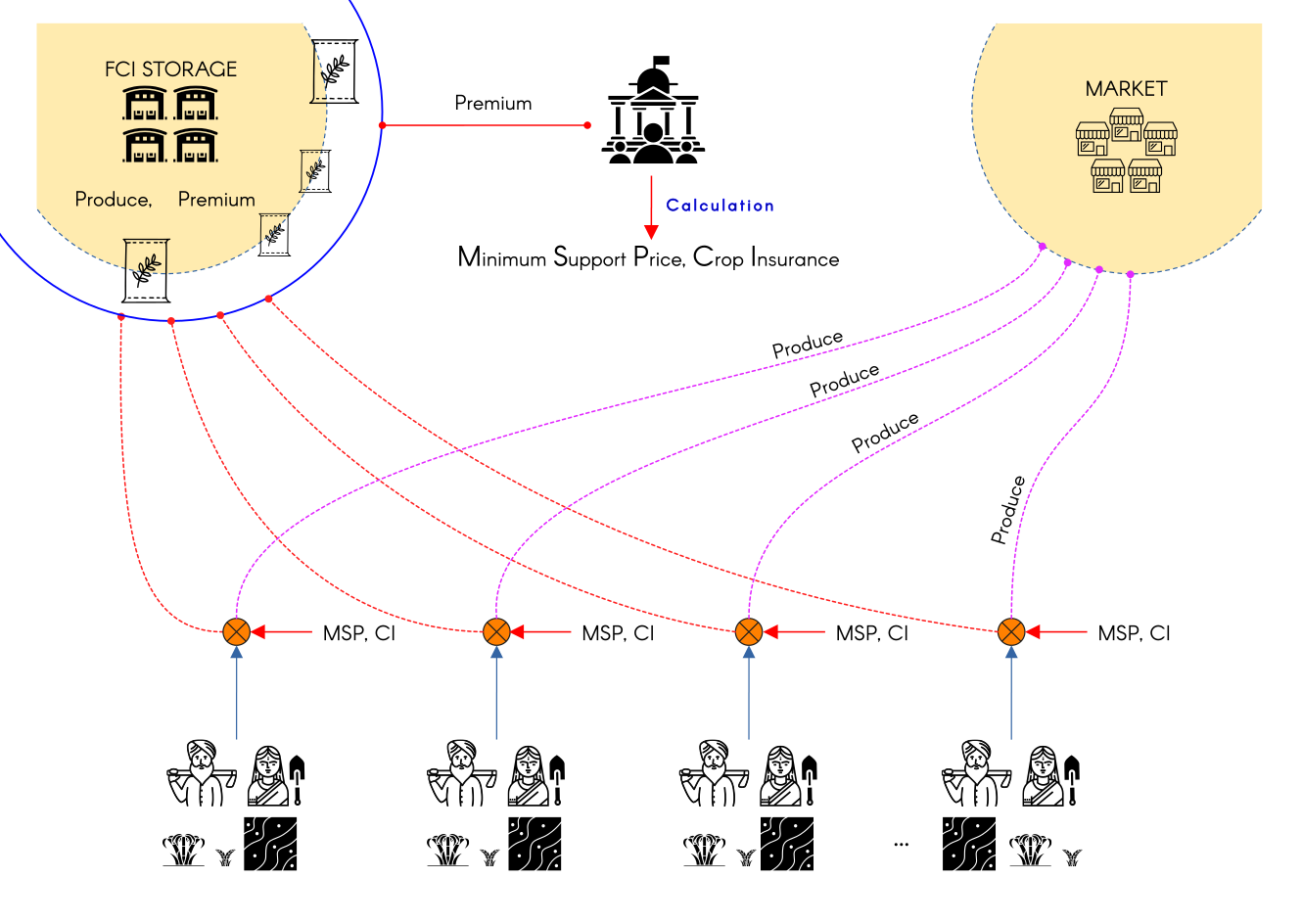

Ideal conditions of flow of produce from land to the warehouses Vs Real conditions with open market in the pursuit of fair support price

Based on the recommended support price driven by calculations every cropping season, farmers are supposed to make their decisions as to where to sell their produce – either to the state procurement machinery or to the open market. The formative objective is to prevent the dependency of the farmer to the vagaries of the open market. MSP is supposed to free them from such market led uncertainties.This also ensures that the supply of food and nutrition needs of the people through the public distribution system is also not subject to the mercies of the market. FCI’s proper warehousing ensure availability, quality and distribution of food that directly impacts the nutrition status of the population who anticipate the delivery of food through PDS.

As of 2022, FCI had more than 1900 warehouses with a total capacity of 362.71 LMT. Storage infrastructure measures in lakh metric tonnes however is commensurate with the physical space it takes to hold the stock. How much of stored food-stock is directed to support the nutritional requirements compared to stocks routed to the speculative food market is dependent on the measure of the net storage. Availability of space to store procured produce on a first come first serve basis for every season influences how much could be stored and distributed. This storage factor is dependent on the physical floor space for procurement in the FCI godowns, where the farmers expect to deposit their produce. Recent protests by the farmers in the country, were meant to demand a consistent legally assured guarantee of both state and private procurement and a fair calculation of the minimum support price for each cropping season.

Thus the existing infrastructure, institutions that monitor, and regulate the economy of agriculture has to balance between the nutritional flow and market dynamics. The bureaucratic practice of these institutions are marked by periodic surveys, market analysis, modeling, and calculations. With the current technocratic push for automation, in the name of guaranteeing objective measurement, there is a new forms of digital machinery such as the use of unmanned aerial vehicles, Hyper Spectral Imaging, precision farming, GIS (Geo-Spatial Information Systems) driven data monitoring and delivery and big data analytics, and of course the use of AI in all these. The substitution of the bureaucracy with these is supposed to remove arbitrariness of human centered measure, grading and calculation. The machine shall now ensure objectivity and fairness, un-corrupted by the human sensory led decision making. The farmers movement in the country are questioning the democratic possibility of demanding justice when it is denied by the regime of measure and calculation.

Farmer’s resistance and the promise of technology

Since almost 70% of the country’s population directly or indirectly depend on agricultural employment,it is important to consider the influence that technocratic apparatus will bear on the socioeconomic fabric of Indian agrarian economy,and therefore on food security and nutrition.Substitution of a huge and established statistical machinery of agricultural management and governance by a digital information technology centered apparatus,drives the need to look back at the history of the relation between the struggle for fairness and the emergence of new technologies. The history of this alignment between the need for just returns to labour in the farms and the elusive promise of technical solution has left behind a heap of ruined hopes.As Mario Tronti reminds us, such a heap of accumulated unresolved issues conflate real needs with more technological interventions.

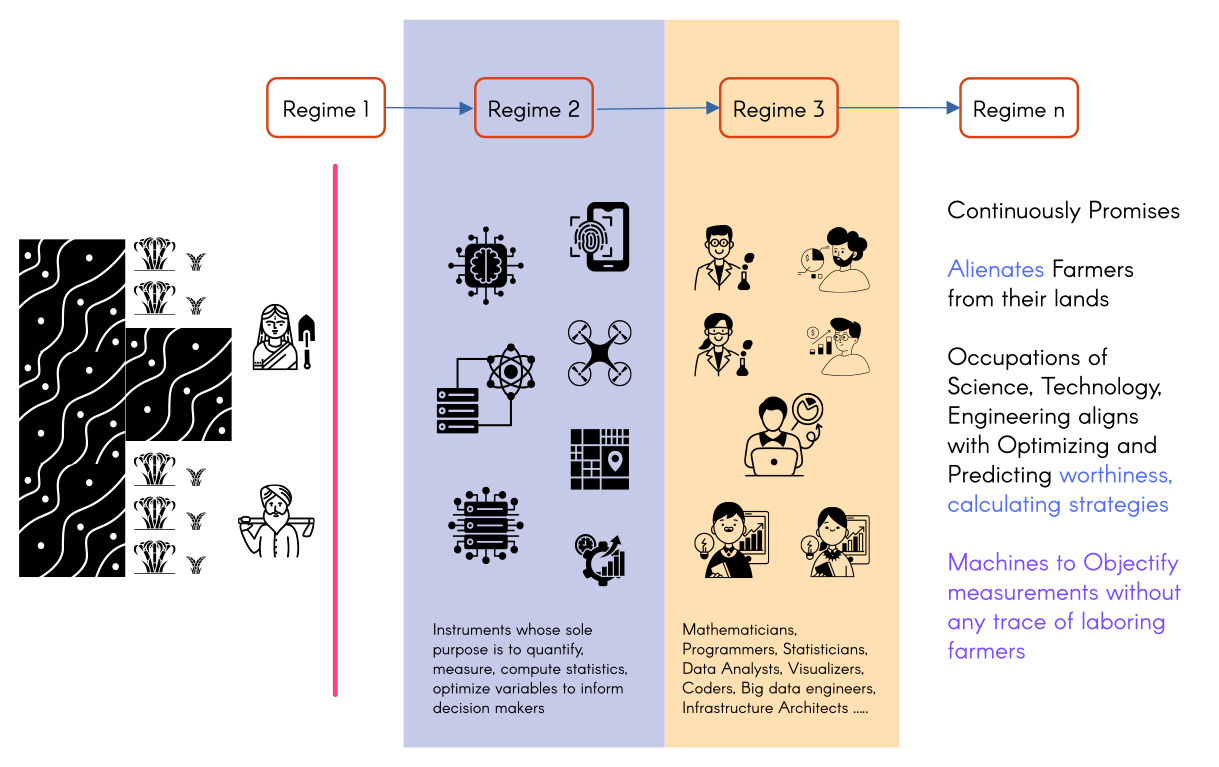

It is evident that new institutions emerged every time with a new technology driven promise, syncing with policy frameworks.

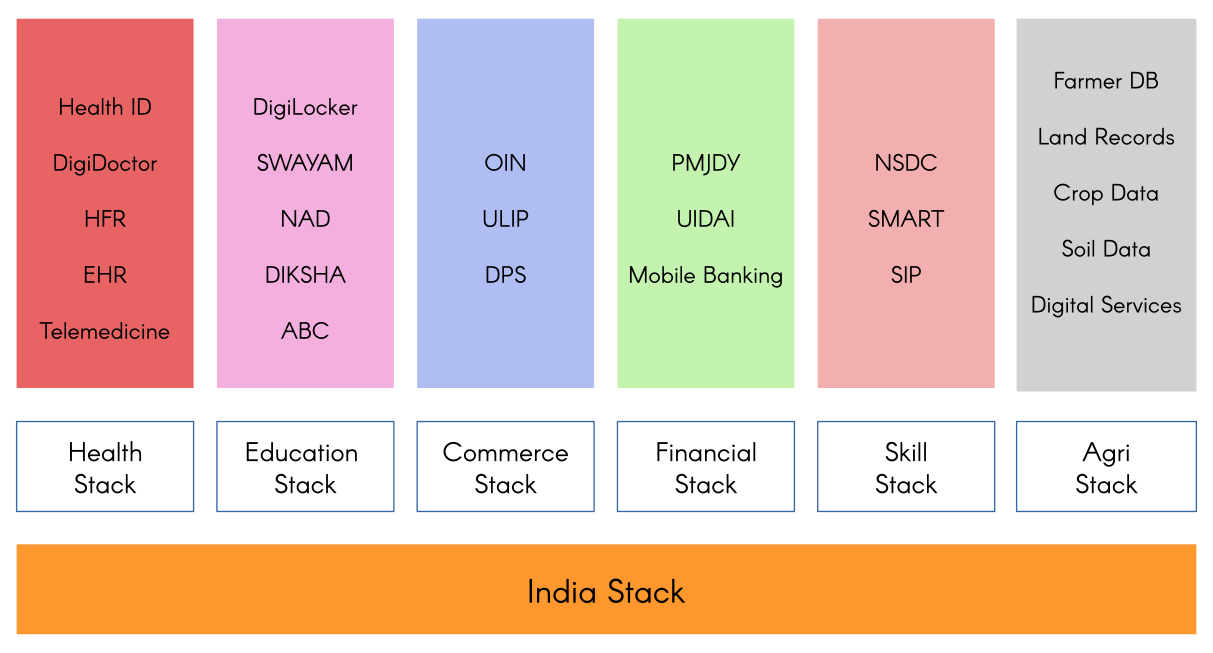

India Stack is the latest institutional promise in such a long history. It is a digital infrastructure regime aimed at transforming the governance of various economic sectors of India.The following illustration of stacks show integration of multiple vertical technology infrastructures.These stacks are anchored by uniquely identifying Indian residents using a biometric authentication apparatus which will connect their record within and across stacks, making it mandatory to access basic welfare.

Part of this digital aggregation of technological monitoring and control systems, is the Agri-Stack initiative. Its stated objectives are to create a unified layer of database of farmers,land and crop. This is visualized as an integrated platform of digital database for every farmer in the country, agricultural land and all possible crops grown. Such a facility is meant to provide all associated services to farmers so that they can access state welfare, financially secure transactions with the procurement machinery and of course, the eternal promise of fair compensation to loss through insurance. Usual excuses such as speed, efficiency, optimization, ready availability,customized solutions and scaling of problems constitute a grand narrative. Here is yet another promise, riding on all previously accumulated and unresolved problems and pending promises.

Promise of Precision and the reality of Extraction

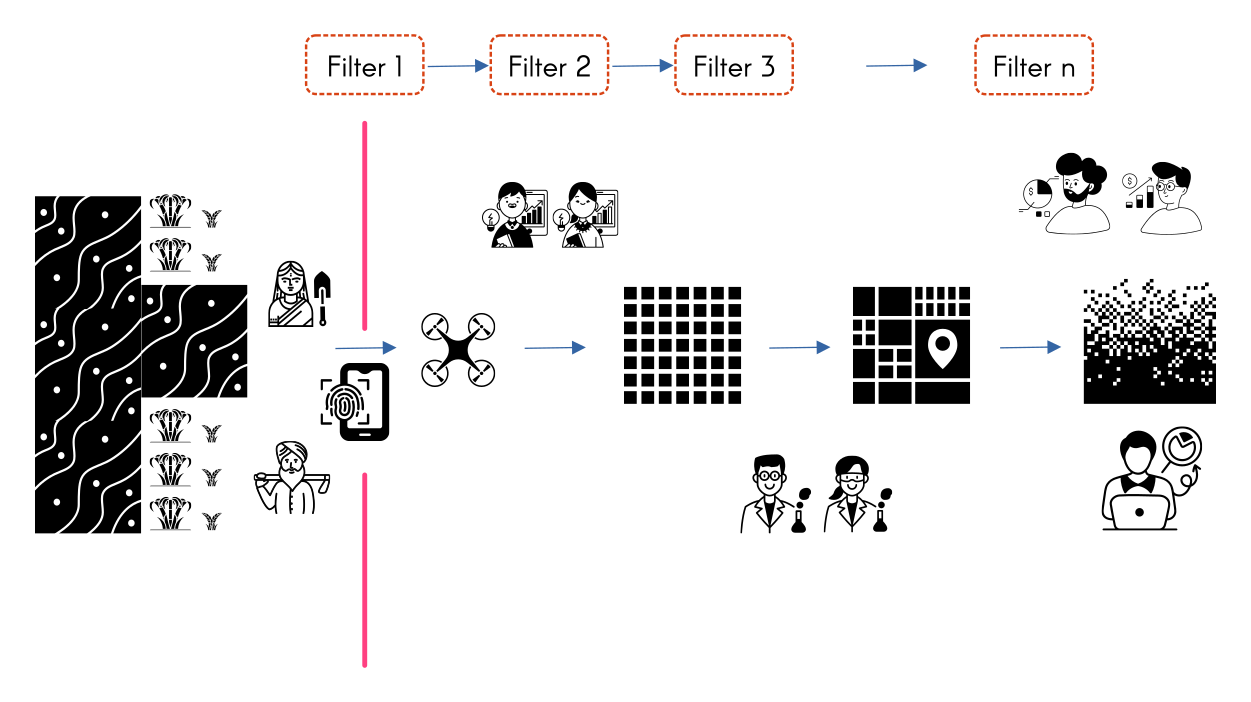

Proportional addition of more elements to the technological apparatus is usually translated as a positive improvement towards more accuracy and precision in service delivery. The above illustration depicts a process of how agricultural produce is quantified through providing unique identity for the farmers, through the quantification of land, soil leading to further abstraction along a chain of measures, when land and crop become pixels in order to be processed as data points. The computing of this large scale data is supposed to be carried out by the public private partnership, which effectively means huge contracts for corporations such as Amazon, Google and Microsoft.

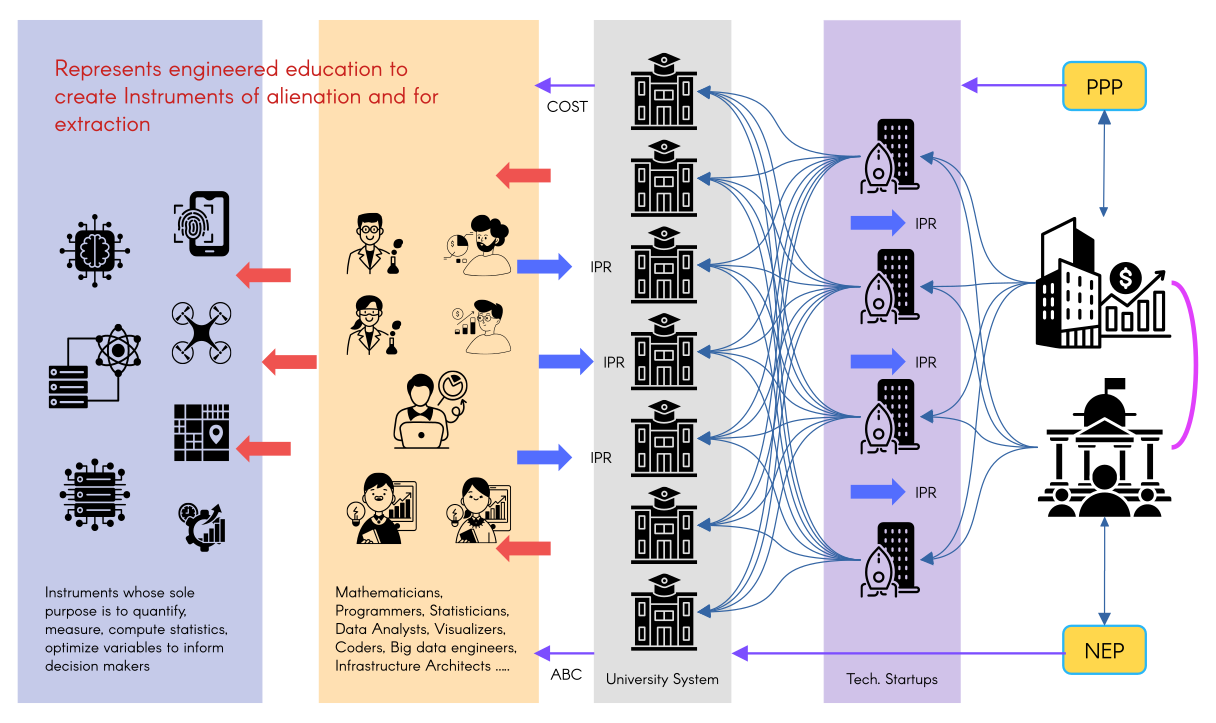

Each node in such processing yield more pixels, indices and metrics which filter and determine value. But in effect, these erase and leave behind the need for just returns for labour, realization of dignity and active democratic participation. This form of abstraction by elimination of variables that are not measurable or quantifiable constitute epistemic asymmetry. This asymmetry is usually relegated as a problem of translation, or even a mere difference in perception. This now is construed as a design problem dependent on who develops computable models, abstracts variables and builds algorithms. This is the industrial landscape of technology startups and associated financial institutional machinery guised as Public Private Partnership (PPPs) who convert problems into symbols, through the manufacture of mathematical models, algorithms, survey instruments, computing architecture for storage, analysis and processing of information. Belief in sample surveys mean making undeliverable promises as a product of statistical errors, which in turn lead to optimizing models, fine tuning data infrastructure and more investment in technology infrastructure.

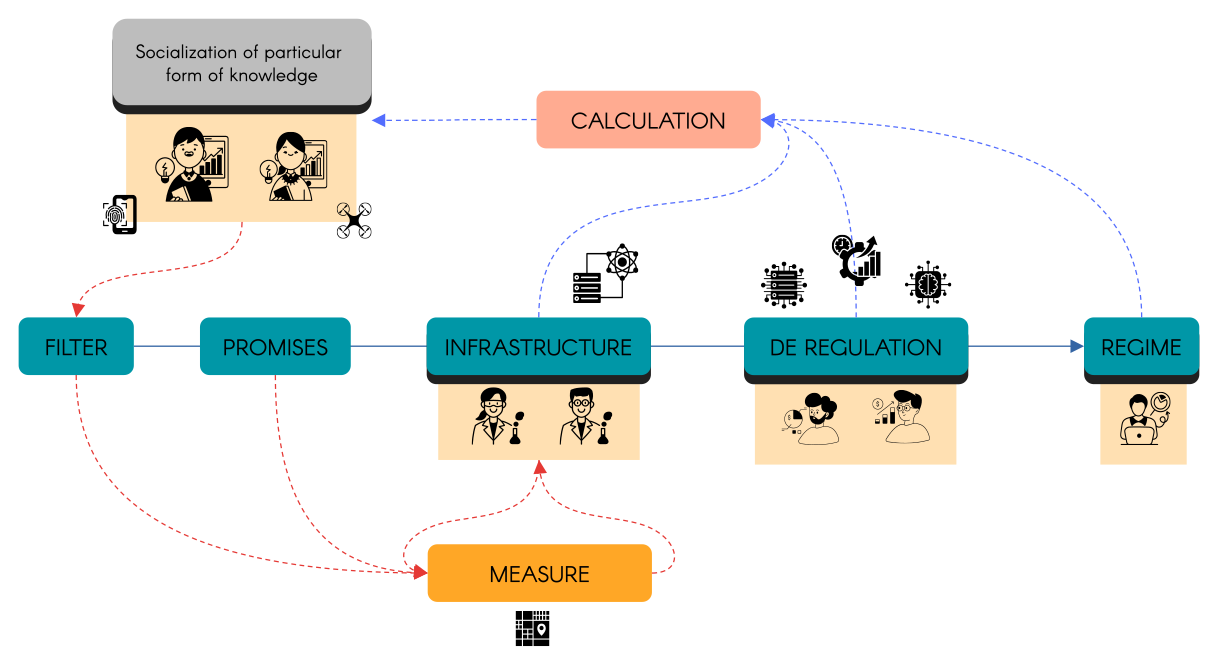

Above illustration shows a more elaborate flow of control from which promises and filters are produced through routine tasks of a a diverse body of knowledge workers who work and operate within the given apparatus. Already alienated from the direct experience of any productive activity, let alone farming or realities of a livelihood dependent on agriculture, these workers are produced and certified by the contemporary neoliberal educational institutions. The complex of filters and sieves of value making then are reinforced in education and work to create regimes of calculation, resulting in value forms, yet again eluding the need for fairness to labour.

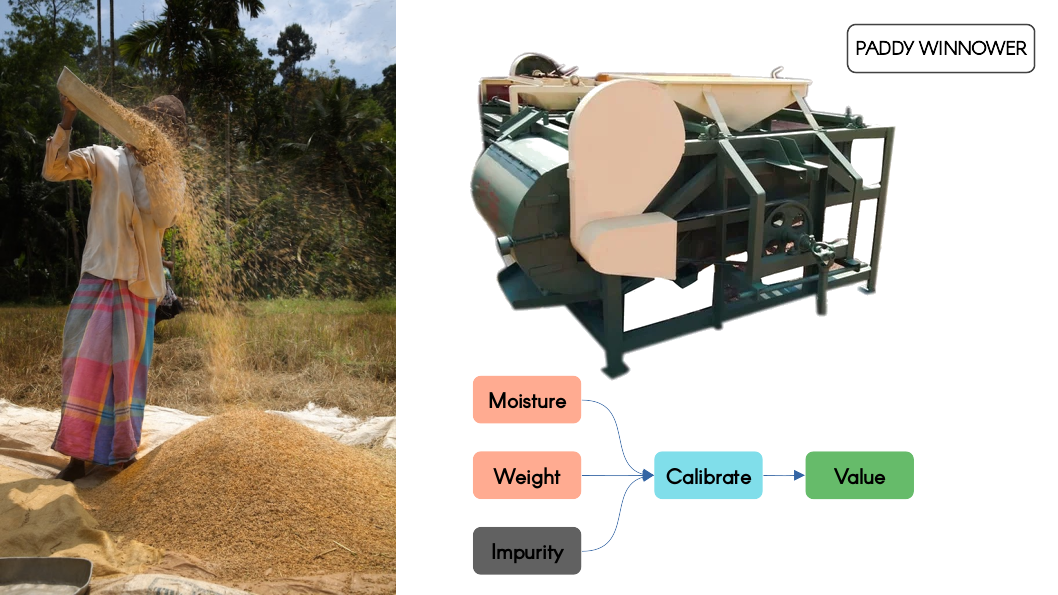

One particular instance to demonstrate the calculation of value can be witnessed at the threshing floor of paddy. The the value of paddy is measured based moisture, weight and impurity. Labour that went into the making of paddy is relegated to mere wages before the threshing. The value chain begins after labour. Calculation of value becomes routine cost and benefit analysis. This is illustrated in the following figure.

Such factors were measured as cost in MSP calculation, which itself is applied on a pan Indian basis without addressing subjective considerations, which dictate the everyday realities of farming. Even the prescribed MSP is usually not provided as demanded by the farmers. However numbers and calculations from research institutions and scientific committees – who primarily depend on statistical measure, data analytics routinely work to advise the government. Science and its calculation infrastructure are by default supposed to deliver fairness to farmer. This belief in state infrastructure and the regimes of calculation need renewed political scrutiny in the current renewal of promise of digital information centered technology infrastructure.

Thus it becomes necessary to understand how the asymmetry is maximized through specific forms of socialization of knowledge and how it informs the construction of cybernetic infrastructures are implicitly sociomorphic.

Sociomorphism in Technology Stacks (Agri-Stack):

The disparity and asymmetry between the designers of of cybernetic planning and that of the workers reflect the social structure. To make it clear, we need to understand that the construction of data driven cybernetic engines like Machine learning and Artificial Intelligence, does not reflect self organizing modeling towards solving problems. The following illustration adds layers to the earlier illustrations that helps in understanding the flow of perception, construction of technological solutions from the completely alienated end of the society that has completely detached itself with the practice of farming and other similar works in the context of Agri-Stack.

Establishment of New Education Policy (NEP) in India leans and supports towards in producing work force (through Academic Bank of Credits (ABC), encouraging vocational courses for particular skill set to match the industrial labour market in service sector primarily) that is suitable for this emerging service industry that attracts more job opportunities with the notion of high paying salaries. This creates a competitive labour market valued as producers of technological apparatus that can be combined in suitable ways to sustain the infrastructure and functioning of technological stacks. The aggregation of such hierarchically and recursively dependent technological growth spins up a speculative market of promises (ensuring flow of promises, filters, and thus new data infrastructures, driving new venture investments which in turn can gain value in financial stock markets) based on simulation/narration of solving social problems just like the ones faced in Indian agricultural sector.

Growth in large number of new private education institutions reflect this path of producing more engineers, mathematicians, logistical workers, technologists, algorithm designers, programmers, statisticians, data scientists, data analysts, data visualization designers, full stack developers, social media influencers, etc.

This speculative growth in diverse forms of jobs making the University education as platforms producing mechanically intelligent problem solvers whose perception work only within the boundaries of abstraction thus losing any possible connection to grounded reality. This situation occurs in the long trail of unresolved problems as manifested in the recurring farmer protests. The other end of the trail is the cultivation of an ignorant and disconnected workforce who care the least about the precarity of farmers despite their own impending precarity. This is the bifurcation that is illustrated in the following diagram.

Given the gendered imagination of Indian agriculture sector, women farmers are unimagined in the general collective intelligence. With this, we can see who bears the burden of failure of promises at the house hold level. Women being the largest target for the Microfinance industry carry the burden of proving their credit worthiness, while maintaining household reproduction through multiple/recursive debt trap. This turns them into commodities for reified financial gains extracted by the microfinance industry all the while keeping household indebtedness as a persistent reality. Curiously, this industry survives with the promise of women’s empowerment and zero collateral based access to credit.

This translates to devaluation of labour against the promise of fair price and just insurance.At the same time,the flow of promises from the technocratic institutions, startups and the fintech industry accumulate their value in the form of heightened play in the financial markets as stocks and portfolios.This forking of value between the farmers and the regimes of promise is illustrated above.This informs the mechanism of extraction of value, which is mediated by the technological stacks,originally deployed to strengthen agricultural infrastructure but in reality, end up as conduits of extraction from the farmers themselves.