One Free Market or Many Unfree Markets

At the time of a global pandemic, when the Indian government should be focusing on delivering health and economic measures, they turned their attention to pass the farm and labor laws that can crush the bargaining power of two groups who together form 90% of the work force in India. This historic ongoing protest is a very clear call by the farmers and laborers to condemn the government’s neoliberalism 2.0 agenda. It is not the so called ‘educated’ upper caste middle class, but exactly this majority who faced the brunt of the reforms in both 1991 and now, are standing undeterred on the streets today. As much as a section of the Indian media and experts would like to portray these protests in silos, it is the consequence of deeply embedded structural inequalities experienced by workers and farmers over the last decade that we, as a society have been a passive witness to.

The 26th of November not only saw the collective mobilization of farmers against the unconstitutional farm laws but also a call to strike by the Trade Unions over the recent anti-labor codes. At the time of a global pandemic, when the Indian government should be focusing on delivering health and economic measures, they turned their attention to pass the farm and labor laws that can crush the bargaining power of two groups who together form 90% of the work force in India. This historic ongoing protest is a very clear call by the farmers and laborers to condemn the government’s neoliberalism 2.0 agenda. It is not the so called ‘educated’ upper caste middle class, but exactly this majority who faced the brunt of the reforms in both 1991 and now, are standing undeterred on the streets today. As much as a section of the Indian media and experts would like to portray these protests in silos, it is the consequence of deeply embedded structural inequalities experienced by workers and farmers over the last decade that we, as a society have been a passive witness to. In addition to the current Farm Laws or Labor codes, there has been a concerted effort of the central government to enforce neoliberal agendas such as privatization of agriculture and other public sectors, substitute social protection programs with private insurance schemes, increase the penetration of FDI and favor bureaucrats and the elite businesses. A quick look at the policies enforced by the Center makes clear their aim to please international creditors, increase India’s rankings on the World Bank’s ease of doing business and boost foreign investment rather than safeguard the interest of the laborers and farmers.

It is not just the farmer’s fight

By introducing the current laws, the central government has done nothing innovative or new, except universally enforcing what was implemented in a few states such as Bihar, UP and MP. The abysmal situation of agriculture in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, is sufficient evidence to see why these laws should not be applied pan India. As voiced by a number of farmers in these states ‘there is a reason why most farmers from Bihar and UP are moving to Punjab. While some of us are able to sell our produce in their mandis, many agricultural laborers find work.’ The condition of farmers in states that do not have state procurement and regulated mandis has only become worse over time and the impact of these laws will also fall on the consumers through rising food prices. In most states where there is no procurement, the difference in wholesale food prices (paid by buyers) and retail prices (paid by consumers) is large. Buyers purchase the farmer’s produce at a low price and sell the produce at much higher prices (to the consumers). On the other hand, farmers in regulated mandis in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh receive 15-40% more than the prevailing mandi prices (due to a floor price set by the State) and consumers pay 15-30% less than retail prices. Universally deregulating the farming sector will also result in a complete erosion of rural employment opportunities – this includes not just farm laborers but also the large number of people employed in the mandis. The only player who would stand to gain with these changes are industries, large mills, private agricultural tech companies and international buyers. A popular name that recurrently occurs amongst the farmers is the increasing presence of Adani Agri Logistics Network who in the last 5 years have set up close to 21 companies, focusing on bulk handling, storage and distribution. One of the main and valid fears of the farmers is, under deregulation, groups like Adani Logistics and Jio will become primary buyers – purchasing bulk food grains, hoarding and selling them at higher prices.

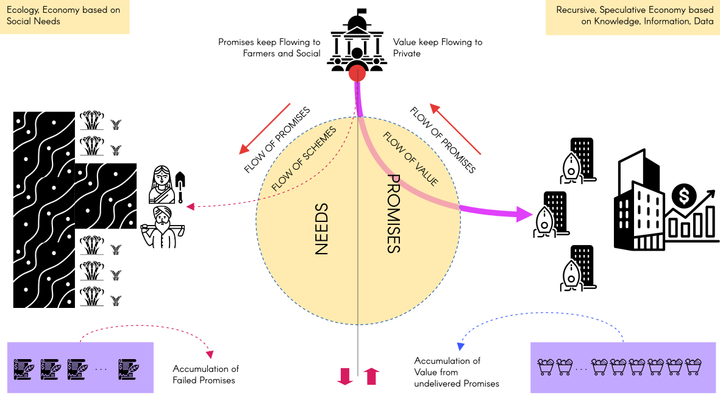

One free market or many unfree markets

A second point that is essential to raise, is the misleading notion of one unified ‘market’, that can eliminate corruption and middlemen who capture large amounts of the market rent. We must wake up to two naive assumptions, first, middlemen (commission agents) are not one homogeneous group – they not only provide multiple services but also have their own hierarchical structures. Second, these ‘middlemen’ and their corrupt practices are not exogenous to the system. Especially in the Indian context where farm holdings are small and scattered, it is extremely challenging for private enterprises to directly engage with farmers. Intermediaries form an important node in the supply chain of many crops and they are therefore, endogenous stakeholders. One of the primary tasks of the middlemen (particularly in areas where state led procurement occurs) is service provision and reducing transaction costs of many farmers with transport and storage. It is true that there are corrupt malpractices undertaken by many intermediaries, however these laws will in no way eliminate such practices but instead create now versions of middlemen. Contrary to the claim that the laws would bring about a unified market, it will actually result in more segmentation of the market (formation of multiple small markets) where without state procurement, the minimum support price (MSP) will only remain a reference to exploit the farmers. The difference is that in these multiple markets, the buyers will have the complete freedom to purchase or hoard crops depending on whether there is more demand or supply without any regulation. The farmers are completely at the mercy of the large national and international private buyers and they do not have the right to contest or judicially fight the exploitation and malpractices. Even when there was regulation under the state APMC Act, many farmers having contract (bonds) with large mills or private buyers found the latter to never abide by it. The buyers often changed procurement patterns based on whether there was a surplus or by using unfair subjective assessments of the produce. Many farmers at the protest compared these laws with their experiences of directly selling to the corporates ‘When large multinational companies such as Pepsico make direct contracts with us eg. potatoes, at the time of harvest they reject half the produce complaining of poor quality, moisture content or size’. Without state procurement, this can also occur in the case of wheat and paddy whereby the prices are determined by these corporations, who will purchase at low prices when there is excess production (high supply) and hoard the grains for seasons when there is less output – in this way the farmer suffers during both times (excess demand and supply).

Neglected areas for reform

The APMC (mandis) complimented by procurement through MSP was considered an essential regulation in agricultural marketing, particularly for small farmers who could get assured returns for their produce within these mandis. It is true that the price setting process under the current APMC Act was not devoid of problems. While the regulation was meant to protect farmers, in many occasions the farmers intern became dependent on the middlemen and commission agents. There was increasing collision between private traders and the commission agents resulting in the farmers to receive a small fraction of the price paid by the consumer, the rest being cornered by the middlemen. However, instead of focusing on strengthening farm collectives, ensuring regular purchase and fair prices for procurement, and investing in rural agricultural infrastructure, the central government in an attempt to wash their hands off the responsibility, implemented the decision to deregulate, privatize and throw the small-scale farmers into the deep end. One area where the government could have stepped in and reduced the growing clout of the commission agents is through credit access and decreasing rural indebtedness. Apart from purchasing the produce and providing other services for farmers, the commission agents are well known to also advance credit to these farmers. Termed as interlinked (interlocked) credit, the indebted farmers have to repay the loan by selling the produce to the same agent. It is this cycle of indebtedness for the small and marginal farmers due to their demand for credit, not just for production but also purposes of consumption that reduces their bargaining power against the agents. Deregulating agricultural markets will not eliminate the agents – as farmers and traders still require stakeholders who facilitate the purchase of crops. What deregulating will do is result in falling crop prices, thereby contributing to the over indebtedness of farmers and their demand for consumption credit.

If indeed the economic or structural power differentials between different market stakeholders, determines the nature of the relations between them, it is possible to ensure the middlemen remains exactly that – a service provider. However, inorder to do this, the focus should be on strengthening the bargaining power of small and marginalized farmers. Why are the farmers from Punjab and Haryana the ones spearheading the protest? It is because they have seen the benefits of having a floor price for their crops, stable procurement by the state and infrastructure (particularly through increasing presence of Mandis). As per the State of Indian Agriculture report (2015-2016), while the all India average area served by regulated market is 449 sq. km, there is large variation in the density across states – from one per 119 sq.km in Punjab to one per 11,215 sq.km in Meghalaya. When globally there is an increasing call to break up big businesses and rethink agri-food supply chains such that the value addition in the supply chain is closer to the farmer, the Indian government is going in the opposite direction. There has been an increasing support for private agri-tech players to procure crops by relying on venture capital – one in nine agri-tech startups worldwide is established in India. Ofcourse, while some of them are emerging in the form of farmer produce organizations or the new age cooperatives, organized retail and food-tech companies are growing rapidly.

Women and protests

Be it the women in Shaheen Baag (protesting the CAA) or the women farmers who are on the streets today, their presence, has startled spectators across the political spectrum and middle class. Female farmers, particularly from Dalit and Adivasi identities have always been invisible either as landless laborers (80% of the rural women who are engaged in farming) or as unpaid labor in their family farms. If it is any group that stands to lose through these laws – it’s the female farmers and laborers. Their invisibility has not only led to the dismissal of their concerns, but also made them the most vulnerable and likely to be exploited under these laws. Even before the laws were passed, the female farmers only indirectly benefited from the mandi system and the MSP – either from the wages paid by producers who sold at the mandi or by using the mandi prices as a signal when selling to private buyers. Apart from employment opportunities and bargaining power (through MSP signaling), most women selling their produce, obtained advanced credit from their buyers. Before the protests on the Delhi border gained prominence, many female farmers had already begun protesting against the farm bills and microfinance institutions who were lending to the women at interest rates as high as 100%. Women in these smaller protests were demanding either cancellation or postponement of their debt repayment, which was mostly used to cover childbirth costs, medical emergencies, and consumption. Over the last month more and more women have been joining the protests – not only asking to repeal of the farm bills, but also issues like the labor codes, privatization of electricity and exploitation by microfinance companies. The female farmers are well aware that corporatizing agriculture, stopping regular procurement, and no floor price from MSP, will only trap them in a cycle of poverty and force them to undertake more unpaid labor, social reproduction activities.

If any group of farmers have lived the perils of privatization in agriculture, it is the women as they never directly benefited from the mandi system. As a means to circumvent the exploitation they faced both in the mandi and private market, women farmers across different states were starting to set up Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO) – where they would not only procure but also sell their produce. Some examples of FPOs are ‘Benishan” established by women farmers in Telangana or Kerala’s Kudumbashree group that promoted weekly women markets – ‘Naatuchanta’. Instead of helping strengthen these movements by providing subsidies, institutionalized credit and assured procurement, the laws will put these groups at par with existing traders and other large corporations – thereby creating an unequal playing field. Here, when the government had an opportunity to actively operationalize their visions of ‘female empowerment’ – they have not only failed at this quest, but are also crushing the existing ecosystem that female farmers tried to build on their own.

Unconstitutionally passed

Finally, assuming that the new laws are going to create free, open markets for farmers or increase employment opportunities for workers, why have these laws been passed without transparency? All the three farm laws fall under the purview of Agricultural Marketing, primarily a state government’s prerogative. In the midst of the COVID pandemic, on September 14, 2020, the central government used the ordinance route and without any multilateral deliberations (the state governments or agricultural unions) brought these ordinances to the Parliament as legislative bills. A similar process was used to pass the labor codes despite multiple trade unions having submitted their objections to it. While the Centre claims to bring in transparency and open markets in the Agricultural sector, the labor codes are meant to bring in labor flexibility to the industries, making it the preferred destination for investment. Thus, both sets of laws, are serving only the owners of businesses or large agri-firms, who can ‘hire and fire’ laborers at will, procure food grains and crops by exploiting the lack of demand or excessive supply in the ‘open markets’.

References :

- https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/three-farm-bills

- https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/agrarian-crisis-punjab-and-making-anti-farm-law-protests

- https://www.newslaundry.com/2020/12/04/why-landless-and-marginal-farmers-are-the-backbone-of-farmer-protests

- https://caravanmagazine.in/commentary/farmers-protests-women-punjab-singhu-tikri-delhi-farm-bills?fbclid=IwAR2JFMU8Vdx50MK9OGgt6cgi60IiR-uZH9GSnOtY26y9lsVyVhPFqxeqK4I

- https://www.indiaspend.com/73-2-of-rural-women-workers-are-farmers-but-own-12-8-land-holdings/

- https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/agriculture/the-invisibility-of-gender-in-indian-agriculture-63290

- https://mronline.org/2020/12/04/the-pillage-of-resources-a-glimpse-into-the-lives-and-labor-of-marginalized-women/

- https://www.behanbox.com/how-the-new-farm-acts-will-impact-womens-work-in-agriculture/