India reached a milestone on October 22, 2021 of managing a health crisis, Covid-19, by administering 1 billion covax dosages to its population. Although the situation was completely different when the Supreme Court of India in a suo-moto case inquired the Central government on vaccine procurements, the dual prices of Vaccines, and its accessibility when the country was reeling under the fatal second wave earlier this year. The progress of vaccination, however, now seems to be on track, and a silver line amid the chaotic times from the start of the Pandemic.

During the last 18-19 months India, and the world has witnessed an unprecedented health calamity that exposed the vulnerabilities of our health infrastructure, and left many people grieving for their losses. It also showed how governments responded to the Pandemic, often disappointingly; India was no exception to this. There were many occasions when governments failed to defend the lives of its people, The Indian government chose to gaslight its public. And one of the tools that it employed was the use and discourse of Mathematical models.

In this article I would present a picture of what transpired during this time through the Covid-19 – the beginning of the pandemic in India, how it affected the Indian population, and what ways the Indian government managed the pandemic – in the context of the rationale, development and use of the mathematical models to ‘track the pandemic’.

The Working Population and the Failure of State

On March 14, 2020 the Indian government declared the pandemic as a notified disaster, as the first Covid-19 cases started appearing in India. Prime Minister of India, in his address to the nation, announced the first nationwide lockdown on March 24, 2020. The sudden announcement of the lockdown caught everyone off-guard. Migrant workers especially suffered from this lockdown. An article in Telegraph succinctly captures impact of the restrictions and the limitations of economic activities that many migrant workers were dependent upon: “The 21-day nationwide lockdown, announced with less than four hours’ notice at 8PM on March 24, sparked an exodus of migrant labourers from cities across the country. Some crammed into buses and trucks and left while many others walked hundreds of miles, deciding that was better than staying on in a city where they had no work or money for food.”

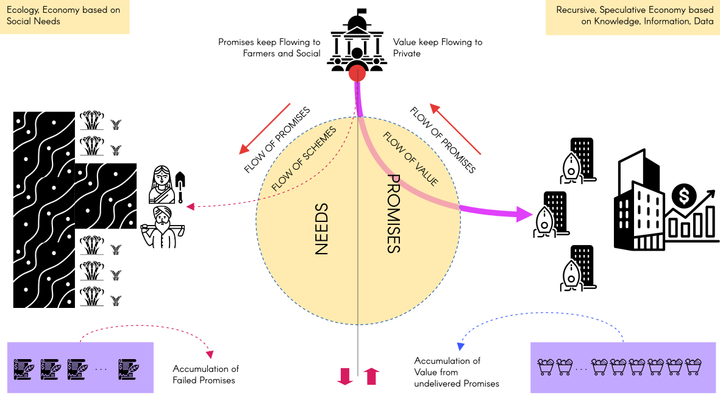

Both the Union and many State Governments blamed this movement of workers on rumours or fake news; the Union government later claimed that the state governments were asked to use the Disaster Relief Fund to provide food, shelter and other amenities to the migrant workers. The workers preferred to return to their native places instead of staying back where they were promised ration and shelter in the face of the threat created by the ongoing pandemic, no jobs as a result of the lockdown, and the uncertainty how long the lockdown would last.

State governments did not allay their fears; and the media was abundant with the pictures and stories of Migrant workers with their families and small kids walking several miles of distances without food or rest: “These workers faced every kind of hardships from walking on foot hundreds of thousands of kilometres with minimal availability of food and water and being given inhuman treatment like beating with lathis to sprayed with disinfectant.”

Contrary to the claims by the Union and the State governments, migrant workers hardly received the ration or cash as promised: “50% of workers had rations left for less than one day. Seventy two percent of the people surveyed said that their rations would finish in two days. Ninety six percent had not received rations from the government and 70% had not received any cooked food. Around 98% had not received any cash relief from the government.”

The inhuman treatments only justified their fears and urges to go back to their native states. Many workers and their family members died during this agonizing journey. Many accidents in which the travelling workers died were reported. In the middle of the hot summer, many died due to starvation and heat. The non-Covid deaths during the period of the beginning of lockdown in late March and to July (by which time the national lockdown was lifted but there were varied restrictions of movements in States.) were counted as 971 according to a report by independent researchers who collect and maintain the data on non-Covid deaths. The public database, which was last updated on July 30, 2020, reports a figure of 991 deaths that happened “due to starvation and financial distress, exhaustion, accidents during migration, lack or denial of medical care, suicides, police brutality, crimes, and alcohol-withdrawal.”

Amid the criticism of unplanned lockdown and the failure to handle the workers crisis, the Union government, through the Ministry of Labour and Employment, responded to the questions in Lok Sabha, in September 2020, that no data has been maintained on how many workers lost their jobs during the lockdown. It also stated that they did not collect any data on the migrant workers deaths during the 68 days period of lockdown, so there was no question of providing any compensation to victim’s families.

The outcrying against the Government(s)’s response to manage the pandemic, as well as other crises that arose due to lockdown, exposed the already vulnerable infrastructures. The public and private health systems were overwhelmed, especially during the Second wave, and the inefficient economic systems robbed the people, especially from the vulnerable section of societies, of their wages, incomes and social security.

Economy versus Public Health

In the middle of the lockdown chaos, another discourse arose. Infosys co-founder N R Narayanmurthy in an interview to Economic Times on 29 April 2020, proposed long working hours post lockdown, and praised Indian government’s response to Covid 19 pandemic, and how the governments had provided food and cash to the daily wage workers. In a question on the status of Indian economy and its deceleration due to the lockdown, He proposed increasing the number of shifts in a company to increase the social distance, for senior executives to work from home to reduce the infection rates. On the question of what kind of reform he would propose to keep the economy on track, he said that the Indian working population should prepare themselves to work 10 hours per day for 6 days a week, ie. 60 hours a week as opposed to the 40 hours work.

In a country where people are overworked and underpaid, Murthy’s comments drew flack. Mr Murthy’s comment on the long working hours came in the midst of many state legislations that sought to increase working hours with proportional payment of wages. Rajasthan, Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh issued notifications on the relaxations of labour laws.

“Amitabh Kant, CEO of the government’s policy think tank NITI Aayog, too has supported the measures taken by Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. The reformist zeal to push through structural reforms will alone lead to “sustainable growth”, Kant tweeted on Friday.”, as reported in an article in Telegraph. These measures were not only met with widespread criticisms but also were challenged in the courts. The Uttar Pradesh government withdrew its notification following a notice issued by the Allahabad high court.

The Mathematical Modelling Discourse

Among many suggestions by Mr. Narayan Murthy in his interview to ET, he became one of the first voices in India to propose the development of a data-driven mathematical model to simulate the pandemic trajectory. This exercise, he proposed, would help analyse the impacts of lockdowns on industries as well as to provide directions to the policy makers to manage the pandemic. With the onset of Pandemic across the world, many scientists and researchers had taken upon the development of mathematical models to evaluate lockdown measures and to direct policy makers to ‘flatten the curve’.

From agent-based models (e.g. this) to the “data-driven” epidemiological models (e.g. this), the exercise of modelling and its various scenario outcomes became central to understanding the course of pandemic and its impacts. It was not until late in 2020 that we heard of the Indian government’s Modelling initiative: to track the pandemic trajectory after the first wave subsided, and to forecast the dates and intensity of the Second Wave.

In May 2020, the Department of Science and Technology (DST) formed a National Covid-19 Supermodel Committee with scientists from various eminent educational and research institutes in India being members of it. In a paper based on the study done under the Supermodel Committee published in October 2020, the authors developed a SAIR (Susceptible, Asymptomatic, Infected, Removed) Model, as opposed to the traditional SIR or SEIR models, to capture the uncertainty around the asymptomatic population. The authors concluded that the lockdown “as a way of greatly reducing inter-personal contact has been very effective in checking the progress of the disease”.

The self-congratulatory tone of the study which represented DST, a body of the Central Government, could be seen as a rationalisation of lockdown measures in retrospect which proved to be deadly to many migrant workers, and was highly criticised. Two other papers, from the same modelling team appeared between October 2020 to December 2020: One explored the uncertainties around Covid-19 infections and an estimate of a herd immunity threshold, and the other discussed the impacts of lockdown and other interventions on the pandemic growth. The most famous one, the SUTRA model, followed steps similar to these studies, and sought to forecast the onset of upcoming waves and rates of infections now.

“The acronym SUTRA stands for Susceptible, Undetected, Tested (positive), and Removed (recovered or dead) Approach. Susceptible, The word Sutra also means an aphorism. Sutras are a genre of ancient and medieval Hindu texts, and depict a code strung together by a genre” as Agarwal et al wrote in their research paper published on arXiv, a pre-publication portal. The authors were also members of the National Super Model Committee and presented their forecasts and analysis to the Government to help them plan the pandemic impacts and interventions. To an untrained eye, the SUTRA model does not seem to be very different from the SAIR Model that was developed and whose results were presented earlier in October 2020.

Barring few logical changes in the equations, how the mathematical model was developed to solve these equations, the parameters and how they were estimated, SUTRA and SAIR models only slightly differ in what predictions/forecasts they are making. The SAIR model was one of the very first modelling exercises by the Super Model Committee under DST, and it had basically concluded that the lockdown did work in taming the pandemic in the first wave, it did not claim to forecast or predict the pandemic trajectory detail.

The Model and The Rabbit Hole

The term “pandemic trajectory” along with “tracking the pandemic” became ubiquitous, but hardly have there been any more insights about it, as in what is it tracking and what it is not. The SUTRA model website, at least to the common public, shows the model results for India, Indian states and districts, and the pandemic course for a timeline – two curves neatly matching with each other in shape, the blue colored one, weekly average data of infections rate, and the other red curve that shows the simulated results based on the data on infections rate. As for the forecast or any prediction, the website only shows a few more data points implying the modelled results of infections in coming days. The simulated results don’t show any confidence intervals, that is normally the practice by the modelling community to represent the results with the uncertainty in the models.

As late August 2021, the news reports were rife with the information on the upcoming third wave, as forecasted by the ‘health experts’(e.g. this). Ironically none of the modellers are epidemiologists or have any background in medical sciences. We were told the results of an optimistic scenario where the emergence or the impacts of a new mutant of the virus would be insignificant. And that that would be even lower rates of daily infections. One could guess this would be because of the growing vaccinated population, more testings, and hopefully a better prepared health infrastructure. They did not, however, present any other scenarios, such as the potential of the public not following covid norms in the coming month to celebrate the festivities, or attend political rallies (UP State election is due early next year).

This ‘optimistic scenario’ has been in contrast to the havoc eventually caused by ‘the new mutations’ in the second wave, and how this had caught off-guard the modelling team. The warnings from INSACOG, the national task force formed to study the pandemic, were ignored: “The warning about the new variant in early March was issued by the Indian SARS-CoV-2 Genetics Consortium, or INSACOG. It was conveyed to a top official who reported directly to the prime minister, according to one of the scientists, the director of a research centre in northern India who spoke on condition of anonymity.” A detailed account of this topic has been covered recently by the New York Times.

The deadly second wave where nearly 3,00,000 people died, was the result of the new strains of the virus, and the lack of robust, sufficient health infrastructures which was not at all prepared for this. The horrid tales and images of the Second Wave in India could only tell how India was managing the pandemic. The modellers and the model were criticised in making wrong predictions, and ignoring impacts of the superspreader events such as Kumbh Mela and the political rallies where no norms of physical distancing were followed, and hardly anyone, including the big political figures wore masks (despite the telling evidence of masks being an effective measure in controlling the spread of the virus and infections).

The criticism from the scientific community pointed out how the compartmentalisation in models ignores the social facts such as the dynamics and heterogeneity of socio-economic conditions, and the access/availability of health facilities. The modellers were also criticised in how they had laid out their modelling equations, and estimated the parameters. The input data and corresponding parameters signified the number of detected cases, number of recovered or dead people.

The Politics of the Model

The SUTRA model also introduced a parameter to mathematise the social behaviour of the spread of the virus, the ‘reach’ to account for the “spatial spread of a pandemic over time”, among other parameters. In this sense also this new model differed from the earlier SAIR Model: “While the SAIR model … is the first one to make a clear distinction between asymptomatic and symptomatic patients, it does make one unrealistic assumption, namely: that all persons in group I are symptomatic.” It is interesting to explore how mathematical parameters mapped the social circumstances. The parameter ‘reach’ could also be understood to account for the conditions created by the Kumbh Mela and Political Rallies that drove people to enhance their social interactions, and thus increase the ‘spatial spread’.

We are unaware whether this exercise was done by the modellers. The criticism was augmented to such levels that we received the very first official communication on SUTRA model, on the Press Information Bureau website implying that the Indian Central and State Governments were consulting the modellers in their policy making decisions. The authors of the communication on the Press Information Bureau website write: “Recent reports in some media seem to suggest that scientists working on the SUTRA model cautioned in March about the second wave but attention was not paid to it. This is incorrect. A meeting was called on 2nd April to seek our inputs by one of the very senior officers of the government coordinating the national pandemic response. We indicated that the SUTRA model predicted the second wave to peak by the third week of April and to stay most likely around 1 lakh daily cases.”

Even if it is correct that the modellers did not caution the government in March 2020, one could question what communication happened between the Super Model Committee by DST and the Government(s) on tracking the pandemic (which could mean both the forecasting the course as well as developing some worst-case scenarios along with the optimistic scenarios), and how much this consultation played in making policy decisions. If any policy decisions were made, what were they? There has been ample silence on these questions and a lot of secrecy on what ways the modelling exercise has been used to inform policy decisions.

Inconsistencies Difficult to Ignore:

In early 2021 when the first and second versions of SUTRA model papers were published, the Kumbh Mela and Political Rallies were at their peaks attracting unvaccinated, untested, and potentially susceptible masses of people. It was the same time when the vaccine production had started worldwide and in India, and front line workers were first vaccinated in India. Amid the heights of second wave, late March 2021 to May 2021, when infections rates reached one lakh per day and a record number of deaths occurred, and the production or procurements of the vaccine started, the modellers ignored to factor the vaccinated population in the model or produce any scenario of the relations of vaccination rate and the infections rate: one may presume that the more people would be vaccinated, the lesser would be infected.

The modellers still did not include the Vaccinated population in the R compartment as for the 3rd Version* of the paper, although the vaccination rate had gained only a significant momentum in June 2021 following the Supreme Court case. R stands for Removed, which includes the population that recovered from the Covid-19 or died from the infection. The Removed category in a way means the portion of the population that may no longer pose any danger of infection to the Susceptible (S) population. If they could include the Vaccinated portion in the Removed category, we do not know how the pandemic course could have taken shape or would take shape.

Despite the glaring inconsistencies in the Modelling exercises and the outcomes reported in public, the modellers continue to play the role of health ‘experts’. We have been presented with countless half-baked discussions on the efficacy of Models, to help both the governments and the people to manage and manage through the Pandemic, as matters of natural facts. Given these apprehensions, one can only wonder what politics foregrounds the mathematical models, and the discourses they generate, to highlight certain things while hiding other things. India’s fight with Pandemic has been rife with such lofty games, ignoring realities, and may not stop any time soon; our only tool to understand the ground situations would be to remain vigilant and continue questioning the discourses we are fed with.

Note: The 4th Version of the SUTRA Model paper was recently published on arXiv on September 27, 2021 with few updates and revised predictions. The authors have mentioned that the SUTRA model predictions have been used by “entities such as the Reserve Bank of India to formulate policy”, though the paper does not elaborate on how RBI utilised the model in their decision. The information on how RBI used the model can be found here.