What contact tracing can mean in a democracy

The recent discussion on contact tracing in the context of the COVID-19 epidemic is intertwined with surveillance technologies. These technologies can be cheaply scaled up and they can also be highly personalized, depending on what databases they can be linked to. Given its importance and rapid acceptance by authorities and Governments in India, there are several important questions that we must immediately ask: What should contact tracing mean to us? How should it be implemented in the Indian context? This requires guidelines as well as a legal framework which should be made public. What if a person chooses not to give some history? Can they be forced? To what extent? Where are these guidelines framed and where are the laws that guide them? Again, for instance, can the police forcibly go through their phone history or can authorities make the COVID 19 patient’s name public? What recourse do people have to this?

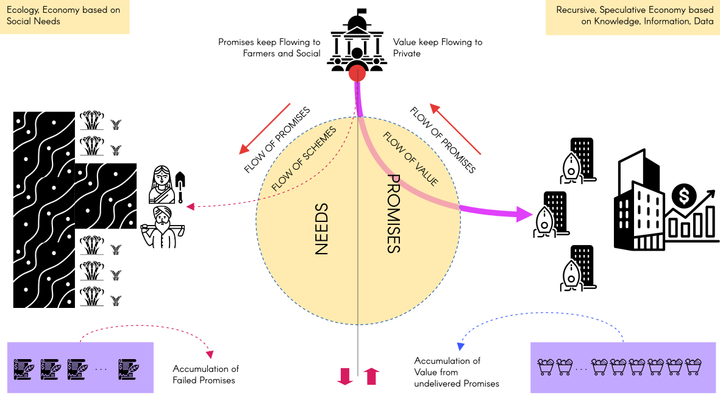

In the interest of democratic freedoms, these technologies should not shift the dynamics of power against the people.

Anyone who has access to the information that contact tracing exercises provide would have a lot of power. If the state, or any other power, has unregulated access to that information, it can harm the democratic fabric of society. There must be regulations that protect the democratic fabric. These regulations should protect the right to privacy, and prevent the use of the data that could lead to social and communal disharmony.

To this extent, it is important that the state develop protections of the information collected along the lines of the laws that protect other information that is collected for healthcare and census:

For example, the Census Act of 1948 maintains that strict secrecy of information collected for the census except for offences directly connected with the census. Census records are also not open to inspection. We feel that the state needs to be very careful when it comes to information about people’s health and location, and ensure that the data not be used against them in any way. The data on the body should respect the right to privacy, and should only be used with full consent.

While the Supreme Court has declared that Indians now have a fundamental right to privacy, it still is not clear what that will imply on the ground. The Right to Privacy includes reasonable searches, but how does it protect people when they are coerced into downloading apps on their phone? Swiggy, Zomato, Grofers have already made downloading the Arogya Setu app mandatory for their frontline workers, while Amazon and Flipkart have recommended their workers to do the same. When employment and use of public transport are conditioned on the use of these technologies, can the use be treated as consensual?

We should distinguish between local Community-level interventions, which can be volunteer-driven, and surveillance initiatives by the state. Recent surveillance and documentation policies of the Indian state haven’t sparked much confidence in people, particularly from oppressed social, ethnic and religious backgrounds. We are living in the times when a large section of Indians – particularly those from the working classes without proper documents, and those from the Muslim communities – are under real threats of losing citizenship en masse. In such times, any effort from the state in terms of ‘health surveillance’ is bound to meet with scepticism and thus even non-compliance. Mass health disciplining is not a legal or policing question, it is a question of mass education, social confidence, and required social, economic and health infrastructure/security that would allow people to follow the rules that are required in such times.

It is also important to realize that the policies that are pursued during the lockdown will interact with other social and political processes. We have a concern about how people are being stigmatized based on the class and community. The ruthless communalization of the epidemic – as seen after the Delhi Tablighi Jamaat demonization – has led to large sections of people losing complete faith in Government-run quarantine facilities or relief centres. This is a clear continuation of the existing political social climate of stigmatizing and demonizing these communities. We have come across several accounts over the last few days where people have said if it comes to a choice between catching COVID19, and getting lynched because of suspicion of someone catching the disease, they would rather prefer the disease itself and succumb to it in silence if required. We are also seeing regular incidences of people belonging to the working classes, mostly members of socially oppressed communities – such as in the case of the returning workers in UP – who are being treated as insects by the administration, under the excuse of ‘countering Corona’. There has been a frantic rise in racist attacks on people with Mongoloid features, who have been branded as cariers of the disease. Social distancing can reproduce the casteist discourse of untouchability.

The role and danger of technologies for contact-tracing:

Around the world, technology-oriented solutions, like the use of downloadable apps, are being developed and adopted, both by central and local governments. . These technologies are scalable and easily to deploy, which encourages their use. However, the scale of their use also introduces many potential misuses, which can magnify the risks of misuse several-fold. To highlight a few:

- Aggregation of data at the centre: Several apps that are currently deployed, including Arogya Sethu, are centralised. All the data collected for contact tracing is sent to and stored in a central server. This increases the dangers of misuse. If contacts of a person infected with COVID-19 have to be traced, why should this information go beyond the local municipality? Why should it be in the hands of the district government, let alone a state or central government? There are many effective models of data use in decentralised systems. Such systems can guarantee that the information stays local. In a country like India, there is a need for us to demand that contact tracing information must stay at the most local possible level

- Patient confidentiality: Data that is used for the sake of protecting people’s health must be treated as private. One guideline we can recommend , is that the information obtained from an app must not exceed the information that can be obtained from the patient by an examination at a hospital by healthcare workers. Given that contact tracing apps are meant to replace physical contact tracing, this seems a reasonable guideline.

- Cross-linking data: Another concern regarding data aggregation is the linking of data from different apps or databases. For instance, contact tracing is often conflated with quarantine adherence. If people volunteer for having their information added to contact-tracing apps, there must be guidelines to ensure that this data cannot be later used to enable containment in quarantine. The risk for technologies with inter-related objectives can lead to gross violations of privacy and could lead to a surveillance state. Incorporating real-time location already enables the surveillance state. There might be some short term benefits, but the inability to get reasoned consent and the risks of such a project is enormous. Many governments deploy data-collecting apps while explicitly guaranteeing that the data collected will only be for one purpose. However, in India, the Arogya-sethu does not have any guarantees. Rather the Arogya-sethu app says that the data “may be retrieved for necessary medical and administrative intervention” and the exact definitions are not clear. It is also unclear which Government departments will have access to this information. Such guidelines must be codified and laws passed at the earliest to prevent misuse and their use for surveillance.

- The path we are on: The sudden and opaque use of surveillance technology in the time of a crisis can set a bad precedent. A public crisis can be a dangerous time to pass laws, as passions run high and critical debate is difficult. Given the use of the technology as a tool of public health, we must make sure that we review the democratic potentials of such technology and not be another weapon for the surveillance state or by private players. We may not be able to turn back the clock on what these technologies will do, but when the crisis recedes, it is critical that technologies, that have become crucial in controlling the spread of the disease, be opened up to the democratic process that respects the rights of all people. New diseases and outbreaks may come in the future, and they cannot be a justification for an intrusive state.

- Growth of a surveillance state and its celebration: Policing technologies and excessive brutality have become spectacles in the time of crisis. Use of force by the police to ‘protect’ the people is not new, but this is perhaps the first time police have been employing modern technology as a response to a pandemic. Recently, a woman from Mumbai was secretly whisked away to a quarantine facility by municipality officials with the aid of police using the centralized surveillance mechanisms. This use of technology is not new, but the indiscriminate use of these tools is worrying. For example, drones, often commissioned through private volunteers, are being employed to monitor and scare people. This is showcased as an innovation, but it only showcases the dominance of the state over the people. In addition to there being little or no public deliberation on such measures and a clear lack of proper privacy protection measures, there is also the danger of these measures becoming normal in the post-lockdown world. In some areas, police have made troll videos based on the footage from drones, which have circulated on social media. These spectacles are circulated to gather public cheer. In the comments section of these videos, concerns are buried under the cacophony of joyous adulations. Sometimes, there are suggestions to employ the service of drones post lockdown to keep social miscreants in check. This can normalize a police state after the crisis.

What do we want in a time like this?

At times like this, we think of the state as a regulator of public activity. The amount of power the state has been able to exercise in this time of crisis is unprecedented. This power might be part of an elaborate social contract, so the people need to ask, what is the state doing to earn this power?

- To prevent a huge toll of life, it is important that the state actively promotes a universally accessible public healthcare system. Surveillance, without testing and protection for those who have tested positive, is not enough!

- The state also needs to take a long term view on healthcare. The policies of the state have not ensured proper access to healthcare across the different classes of society. Even this year, with the crisis oncoming, the state did not take any measures to improve facilities or access. The most successful delivery systems of healthcare have been locally managed systems. Given the sagging role of the centre in developing healthcare systems, we must ask, can we use this as an opportunity to develop community-level healthcare systems?

- The crisis has also demonstrated the inability of the private healthcare sector to respond to these global challenges which affect all people. Thus, we must stress the need to strengthen our public health-care architectures and systems.

- The main tool of the state has been the nation-wide lockdown. This has led to hardship across the country and has disproportionately hurt people who are poor, depend on their daily income, or who have migrated. The state’s response to those suffering has been underwhelming, to say the least. One must ask the question of why technology has not been deployed to address this question? Why is there no app which allows the citizen to easily access the information regarding food distribution services in her/his area? The phone helplines set-up for PDS distribution are still using age-old and outdated technologies, while brand new technological advancements are quickly deployed for central surveillance. Why is there no easy way for every worker to complain regarding non-payment of salary during the epidemic, despite Govt guidelines to the contrary?

- There needs to be a promise by the state to regulate its own surveillance. Without the legal backing and privacy laws to govern contact tracing, both physical and digital, the trust of people in this will suffer. This is counter-productive as it would lead people to prefer to hide the disease than have it traced/tested. Having more trustable procedure with a guarantee of safety and protection is essential to achieve even the stated goal of tracing the contacts and using this information to curtail the spread of the pandemic.

- The other side of surveillance is transparency. It is not clear to the people what the long term plan of the state is regarding the effects of this pandemic. There have been no deliberations, and control has quickly moved away from local spaces to the centre.